26 January 1964

People have often remarked that there appears to be a disproportionate number of Canadian comedians who made it big in the United States. Think of Johnny Wayne and Frank Shuster, Leslie Nielson, John Candy, Dan Aykroyd, Catherine O’Hara, Norm Macdonald, Andrea Martin, Rick Moranis, Mike Myers, Martin Short, and Jim Carey to mention just a few.

One possible reason for this phenomenon is the relative size of the “creative economy” in Canada compared to that in the United States. A 2016 British study by Nesta (National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts) found that in 2011 Canada’s creative economy accounted for 12.90% of Canadian employment, compared to 9.75% in the United States and 8.76% in the United Kingdom. Others have speculated that Canadian comedians owe their success in the United States by spending years honing their craft outside of Hollywood, developing their own unique comedic styles before trying their luck down south. Many earned their chops on SCTV in Toronto. Still others have suggested that Canadians know their American neighbours but at the same time have an outsider perspective that allows for observational humour, impressions, and parody that appeal to Americans.

One comedian who excelled at an early age in impersonations is Rich Little. Little was born in Ottawa on 26 November 1938, the second of three sons of the eminent physician, athlete and boy scout leader Dr. Lawrence “Bones” Little and his wife Elizabeth. The family lived at 114 The Driveway. From a very early age, young Rich was doing impressions for his mates in the St John’s 57th Wolf Cub Pack and at school. At Lisgar Collegiate he did impressions of his teachers, often answering questions in class in their voices. (That must have gone over well!)

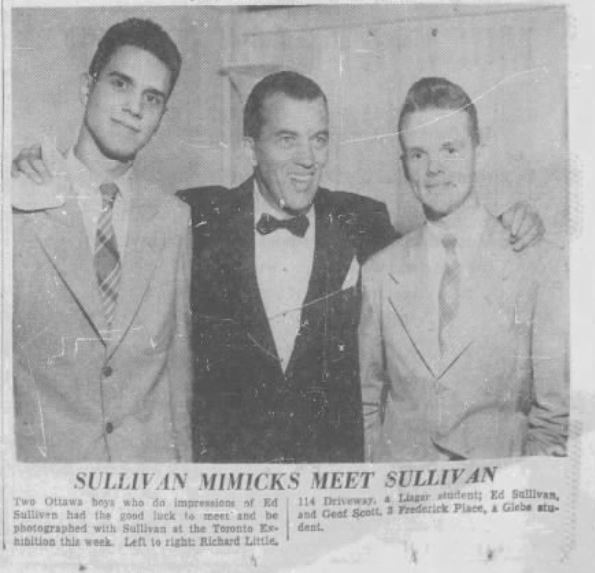

As a teenager, he joined up with Geoff Scott of Glebe High School to do comic impersonations at schools and other local events. In late August 1955, young Rich, age sixteen, and Geoff, age seventeen, travelled to Toronto to see Ed Sullivan who had flown in from New York City to host the Canadian National Exhibition and introduce Marilyn Bell who had swum across Lake Ontario in 1954 and who had just swum across the English Channel. Sullivan was also in Toronto to scout out new talent for his show. Somehow, the boys managed to speak to Sullivan and even get their photograph taken with him. The duo also did some impersonations for the variety show host. Little reported that Sullivan’s poker face broke into a smile saying “Boys, you have some great imitations there. But you lack audience experience. Come back in two years.” Little said that meeting Sullivan was the “thrill of [his] life.”

Little and Scott took Sullivan’s advice to heart and began to perform wherever they could. In November 1955, Little provided entertainment at a parish dinner of the St. George’s Anglican Church. The following year, the duo performed at such events as a picnic for the handicapped in Aylmer, an open house at Connelly Motors in Westboro, and a springtime party for the Ottawa Philharmonic. In addition, they were introduced to radio listeners to Ottawa when Gord Atkinson of radio station CFRA asked them to perform on his show.

Little and Scott got their first big break in February 1956 when they were invited to be one of the acts on the CBC television show Pick the Stars in which a panel of celebrities judged up-and-coming entertainers for cash prizes. The show was hosted by Dick MacDougal. With Little doing great Dick MacDougal and Ed Sullivan impressions, the duo came in tied for first place despite their “nervousness that made them look a shade amateurish,” according to the Ottawa Journal. However, the reporter added that Little and Scott were “a good deal funnier” than Joey Bishop who the CBC had hired at a cost of $2,500 to make a guest appearance on the Denny Vaughan Show, a musical variety series. Prophetically, the newspaper said that Little and Scott had the ability to become great comics should they choose a career in show business. Their appearance on Pick the Stars led to a call to perform from the Gatineau Country Club, the premiere night club in the Ottawa area. However, Little’s parents put their foot down with a firm “no!” After all, Rich was only 17 years old. However, the duo got more gigs on CBC television, including an appearance on the Jackie Rae Show in April 1956 where Little introduced his Charlotte Whitton (Ottawa’s mayor) impression to a national television audience.

As well as doing impersonations, Little got in as much radio and acting experience as he could. While still at school, he worked at CFRA during summer vacations doing everything, including a woman’s show called Helpful Hints for the Homemaker which apparently included one helpful hint for bald men: “Pour sour cream over the scalp twice daily; rub vigorously.” Little also performed in countless plays at the Ottawa Little Theatre and Ottawa’s Children’s Theatre. In a 1955 production of The Tinder Box by Hans Christian Anderson, Little was “third dog.” He was later the “sandwich man” in Pinocchio. In 1958, he played summer stock in North Hantley, Quebec in which he did the lighting, staging and sound, in addition to acting. Also that year, he won best actor in the Eastern Ontario Drama Festival for his role as “Bo Decker” in the play Bus Stop. By the early 1960s, he was doing two or three plays annually, with the view of eventually making the stage his career, with his sights set on Broadway.

While Rich Little and Geoff Scott performed frequently together during the late 1950s and early 1960s, they eventually went their own ways. Following his graduation from Glebe High School in 1957, Scott became a staff reporter at the Ottawa Journal. Two years later after leaving Carleton University, he joined CHCH-TV in Hamilton, where he became the face of the station. In 1978, he entered a new profession as a federal MP representing the riding of Hamilton Wentworth for the Progressive Conservative Party, a job he held until 1993. He died in 2021.

As for Little, after his graduation from Lisgar Collegiate, he took a job at the Smiths Falls radio station CJET where he had two shows daily, doing take-offs of popular television programs. One episode featured a Zorro take-off called “The Stroke of Burro,” in which “Peter Lore” played the burro. It also featured “Jimmy Cagney” and “Charlotte Whitton.” In 1961, he had his own show on CBOT, CBC’s Ottawa station, called Folderol—a half-hour program of light humour and interviews that aired at 6:00pm. The show also starred the Ottawa folk singer Tom Kines, and Jim Terrell who handled “helpful hints for the handyman.” He also formed a partnership with Joe Potts called Little-Potts Productions, selling commercials, station breaks and impersonations to radio and television stations. As well, he continued to hone his stage impersonations at Le Hibou, Ottawa’s renowned coffee shop, and the Gatineau Country Club where he was now old enough to go. Among his impressions were President Kennedy, Prime Minister Diefenbaker, “Mike” Pearson, and Charlotte Whitton.

So good was his Whitton impersonation that in an Ottawa Journal article Little said that he frightened Lloyd Francis, one of Whitton’s “punching bags” on city council. It seems that while Little was driving down Elgin Street one Sunday, he pulled up alongside Francis who was in a car in the lane beside him looking at the construction of the Queensway overpass. Francis, who was oblivious to Little’s presence, almost jumped out of his skin when Charlotte Whitton’s voice shouted at him “Why don’t you look where you’re going, you stupid oaf!”

Through 1962 and 1963, as his popularity rose, Rich Little began appearing on many Canadian radio and television programs, including the Tommy Ambrose Show, and the Pierre Burton’s Show, television specials such as Little’s take on Charles Dickins’ Christmas Carol on CRFA, and a CBC show called Six for Christmas, as well as hosting a regular three-hour CRFA show, six days a week. He also released with Les Lye and Elsa Pickthorne his first album called My Fellow Canadians that spoofed well-known Canadian personalities. The record was a huge success. Mike Pearson, the leader of the Liberal Party, was a good sport about Little’s imitation of him, accepting an autographed copy of the album from Little. However, Prime Minister Diefenbaker and his wife Olive were not amused, advising the record company that neither were interested in receiving a copy.

Expecting to premiere excerpts from the record on the Tommy Ambrose Show in late February 1963, it ran afoul of the spring 1963 federal election. While Little’s impersonations were reportedly neither particularly political or controversial, CBC cancelled the program owing to “the troubled political scene and election campaign.” Public reaction to the news was swift; if anything, it boosted Little’s profile and popularity. A St John NB radio station declared a “Rich Little Day,” playing excerpts from the album and other Little material through the day.

A second album called Scrooge and the Stars, was released in mid-November 1963. It featured the voices of popular American entertainers, including “Jack Benny” as Scrooge and “Ed Sullivan” as the Ghost of Christmas to Come. “President Kennedy” featured as the Ghost of Christmas Present. Just a few days after the album’s release, tragedy intruded into the mirth. President Kennedy was assassinated.

Rich Little’s work on CBC and his records brought him recognition in the United States. He reportedly auditioned for The Jimmy Dean Show in 1963, thanks at least in part to two Canadian writers for the show, Frank Peppiatt and John Aylesworth. But it was no avail. He also auditioned for NBC’s Tonight Show. In an interview, Little recalled that the producer said, “Okay, you’re Rich Little from some place on the Arctic Circle. Make me laugh.” He didn’t get a guest spot, the producer apparently underwhelmed by Little’s sketch about Jack Benny’s birthday party attended by Fred MacMurray, George Burns, Rochester, Alfred Hitchcock and other US celebrities.

1964 was Rich Little’s breakout year in the United States. After coming off of an appearance on the Juliette Show in Toronto in early January, he went to Hollywood to audition for the Judy Garland Show. Again, the opportunity to audition came from John Aylesworth who had seen his try-out with The Jimmy Dean Show and was now a writer for Judy Garland. He had also been greatly impressed by Little’s two comedic albums. Rich Little appeared on 26 January 1964, along with Martha Raye and Peter Lawford. (Rich Little on Judy Garland Show.) Unfortunately, Little’s family and friends probably didn’t see the show when it aired on CBS, unless they had a special aerial to pick up the signal from Watertown, New York. Cable television was not yet available in Ottawa.

From that point on, there was no looking back. Rich Little was now a bone fide star. For the next twenty years or so, he was on the top of his game, appearing on sit-coms, variety shows, including the Dean Martin Show, The Ed Sullivan Show, The Jimmy Dean Show, The Kopycats and The Julie Andrew’s Show. (Here is a 1967 CBC interview with Rich Little: CBC interview.) During the 1970s, he was a regular on the Dean Martin Celebrity Roasts, and became famous for his impression of President Richard Nixon. As well, for a time he was a regular on The Johnny Carson Show.

When his television career went into decline, Rich Little took on the nightclub scene in Las Vegas. In 2024, at 85 years of age, he continues to perform at the Tropicana.

Rich Little was made an Officer of the Order of Canada in 2022.

Sources:

CBC News, 2018. “Rich Little looks back on his time at Lisgar,” 4 May.

Globe and Mari, 1955. “At the CNE: Swimmers Flashback for Sullivan,” 25 August.

History of Canadian Broadcasting, 2024, Rich Little (1938-).

Nesta, 2016. Creative Economy Employment in the US, Canada and the UK.

Official Rich Little Website: The Man, The Voices, The Legend, 2024.

Ottawa Citizen, 1955. “Come Back Later Boys Sullivan Tells Ottawans,” 1 September.

——————, 1955. “No Place For Adult Mind At Theater For Children,” 21 November.

——————, 1955. “10 Turkeys Carved As Parish Holds It’s First Family Dinner,” 28 November.

——————, 1956. “Who Are The Servants And Who The Masters?” 15 February.

——————, 1956. “Tonight is Open House at Connolly Motors,” 27 June.

——————, 1956. “Dedicate Bus At Picnic For Handicapped,” 13 August.

——————, 1962. “Televiews,” 20 December.

——————, 1963. “PM cook to record spoof,” 24 January 1963.

——————, 1963. “Gord Atkinson’s showbiz,” 31 August.

——————, 1963. “Curtain Raisers,” 19 November.

——————, 1963. “Capitol album,” 3 December.

——————, 1964. “Show business with Gord Atkinson,” 11 January.

——————, 1964. “Show ‘biz’ notes, 1 February.

Ottawa Journal, 1956. “TV and Radio,” 7 March.

——————-, 1956. “Pinocchio Final Play For Children,” 24 March.

——————-, 1956. “TV and Radio,” 19 April.

——————-, 1956. “TV and Radio,” 3 April.

——————-, 1957. “Mailbag,” 27 April.

——————-, 1958. “”TV and Radio,” 31 October.

——————-, 1959. “TV and Radio,” 19 May.

——————-, 1961. “Highlights CBOT,” 30 September.

——————-, 1961. “Folderol,” 1 December.

——————-, 1961. “CBOT Highlights,” 2 December.

——————-, 1961. “Me, Jim Tom ‘n’ Folderol,” 23 December.

——————-, 1962. “Girl About Town,” 24 March.

——————-, 1962. “Even on Sundays,” 27 September.

——————-, 1963. “Comedian Caught By CBC’s Cancellation,” 16 February.

——————-, 1963. “TV and Radio,” 22 February.

——————-, 1963. “TV and Radio,” 27 February.