30 September 1965

Over the years, Ottawa has lost many iconic neighbourhoods and buildings through the efforts of the National Capital Commission (NCC) and its predecessors to beautify the city. The best known is the razing of LeBreton Flats during the late 1960s, only for government to leave the former neighbourhood fallow for decades. Great swathes of Lowertown were also torn down in the name of urban renewal. Previously, historic Upper Town disappeared under the wrecking ball to be replaced by the Supreme Court and other government buildings. The government expropriated the Russell Theatre and Russell Hotel in 1928 to make Confederation Square. Ten years later, it levelled the old Post Office and the old Knox Presbyterian Church to make room for the War Memorial and to widen Elgin Street. (Prime Minister Mackenzie King, a staunch Presbyterian, apologized to church members for the Church’s destruction.) The former Supreme Court building on the side of Parliament Hill was knocked down in 1956 to build a parking lot. Most recently, the Daly Building was demolished in 1991 after years of neglect. As well, many of today’s cherished historic buildings, including the West Block on Parliament Hill, Union Station, Elgin Chambers at the corner of Sparks and Elgin Streets, and the Museum of Nature, were once slated for destruction but were spared only by the vagaries of government planning or pinched government budgets.

The Roxborough Apartments was another NCC victim.

Construction of what was to become Ottawa’s largest and most desirable apartment building began in the spring of 1909 on northern side of Laurier Avenue close to Elgin Street. It was owned and built by Imperial Realty of Ottawa. Mr. H.C. Stone of Montreal was its architect.

No expense was spared in the Roxborough’s construction. Its basement sat on a steel reinforced concrete slab three feet thick. The frame of the fireproof, eight-storey building contained more than 600 tons of steel. Its external walls were made of brick and stone, with stone being used on the first two storeys and brick with stone trim on the upper six stories. Interior walls were soundproofed.

There were eighty suites, ten per floor. There were “bachelor” suites consisted of two or three rooms. These suites did not contain kitchens. (Apparently, bachelors were incapable of cooking for themselves so kitchens were unnecessary.) The larger “light-housekeeping” apartments were suitable for families. These suites were equipped with a kitchen, a butler’s panty, and servants’ quarters. Parlours and dining rooms had fireplaces.

The apartment building was designed as a figure eight, permitting all rooms to have windows; there were no interior rooms. An elevator ran through the waist of the building. On the ground floor was a dining room for tenants, a marble vestibule, a lobby, furnished with comfortable chairs, tables and carpets, and an adjoining waiting cum writing room. Tenants could enjoy the views from the building’s roof garden. In the basement was the caretaker’s suite, a large kitchen and laundry, the latter fitted out with the most modern drying facilities. There was also a mail chute for the convenience of tenants.

The interior woodwork, including floors, was made from top quality red oak, sourced from the New Edinburgh Mills of W.C. Edwards. Each apartment door was made from a single panel of five-ply red oak. Interior halls were also panelled in red oak, and ornamented by pilasters decorated with hand carved capitals.

Apart from the first-rate physical environment, what distinguished the Roxborough Apartments from other apartment building of the time was its amenities. Its apartments featured all of the most modern and practical conveniences of the age. In addition to maid service, the Roxborough had top-of-the line plumbing, heating and ventilation systems. A water filtration plant ensured the cleanliness of water delivered to tenants. (This was a considerable health and safety feature as municipal water, which was drawn from the Ottawa River, was not chlorinated at this time. Each year many fell ill or even died from water-borne diseases.) Hot-water radiators provided heating to the apartments, their temperature settings under the control of the tenants. The building had its own telephone exchange provided by Bell Telephone. As well, kitchens were equipped with refrigerators, linked to a central refrigeration plant constructed on its own foundation to eliminate potential vibrations. (This was years before the home electric fridge became available. At this time, most people, if they had anything, made do with ice boxes, with ice delivered weekly by the iceman.) Each apartment also came equipped with a central vacuum cleaning system. Residents ate breakfast in “The Palm” dining room on the ground floor, or they could order meals delivered to their suites.

The Roxborough opened its doors on 1 May 1910. Its eighty apartments were quickly leased to Ottawa’s great and good—prime ministers, cabinet ministers, senators, MPs, judges, diplomats, etc. It was the place to live, just a short walk from Parliament Hill.

One famous tenant was William Lyon Makenzie King, who had an apartment from 1910 until January 1923 when as prime minister he moved to Laurier House which he had recently inherited from Lady Laurier, the widow of Sir Wilfrid Laurier. In his diary dated Wednesday, 10 January 1923, Mackenzie King wrote: “I am spending my last night in the rooms at Roxborough in which I have lived since 1909 [sic]. Their associations are very sacred to me and I feel as if I was parting with something akin to a very dear friend. I love the quiet and comfortable atmosphere; the notes of beauty and refinement are all a part of what is most dear to me.”

King was not the only prime minister to call the Roxborough Apartments home. Sir Arthur Meighen lived there as did Louis St. Laurent, before he moved into 24 Sussex Drive in 1951, following the home’s purchase and renovation as the official residence of Canada’s prime minister. John Bracken and George Drew, Conservative leaders of the Opposition also resided at the Roxborough. Lady Byng, the widow of Lord Byng, Canada’s governor general from 1921 to 1926, lived there through World War II, persuaded by her Canadian friends to weather the conflict from the safety of Ottawa. Governor General Georges Vanier was also a Roxborough resident before moving to Rideau Hall.

Life at the Roxborough went on serenely until January 1965 when the NCC expropriated the property to make way for a proposed $20 million Museum of Human and Natural History to replace the Canadian Museum of Man and Nature (now known as the Canadian Museum of Nature) located on McLeod Street. Residents and heritage advocates were outraged, especially as the site of the Roxborough was not needed to construct the museum, but rather was to be used for landscaping.

H.W. Herridge, the MP for Kootenay West, presented a petition to the House of Commons on behalf of the Roxborough’s staff and residents, excluding residents Finance Minister Walter Gordon and John Nicholson, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, who weren’t asked to sign the petition to avoid embarrassing them. Petitioners cited the historic nature of the building, and proposed that it be used as a residence for official government guests, a Canadian version of Blair House in Washington D.C. One of leaders of the resident group fighting the destruction of the Roxborough was Mrs. Adolphe Caron, the widow of the clerk of the Senate and the daughter in law of the late Sir Adolphe-Philippe Caron, Minister of Defence and Militia in the government of Sir John A. Macdonald. Mrs. Caron, then almost 90 years of age, had been a resident of the apartment building since 1913. She recalled seeing Mackenzie King pushing his mother in a wheelchair through the Roxborough’s hallways.

Despite the high-power pressure, the petition failed. The NCC formally bought the building for $1,450,000.

For a short time, it looked like the Roxborough was going to be reprieved owning to a freeze on government construction as an anti-inflation measure announced in June 1965. However, two months later, Public Works Minister George McIlriath ended such hopes, saying that all tenants must clear out of the building by 30 September 1965. According to once secret Cabinet documents, the decision to proceed with demolition was due to the site being needed by the contractor building the nearby National Arts Centre.

It wasn’t only Roxborough’s residents who had to vacate. The order also applied to La Touraine, arguably Ottawa’s top restaurant at that time, that operated out of the former tenants’-only restaurant on the ground floor. La Touraine had an international reputation, hosting and catering to innumerable weddings, and diplomatic events, feeding such luminaries as HM Queen Elizabeth II, HRH Princess Margaret, Winston Churchill and General Charles de Gaulle. In the last five years of existence, it had served close to a quarter million meals. So popular was La Touraine that the Danish Embassy in Washington would ask it to cater dinner parties.

On the night of 30 September, La Touraine hosted a farewell dinner for two hundred patrons. Flowers and candles decorated each table. Head chef Hlinovski served shrimp cocktail, consommé with sherry, baked beef tenderloin with Burgundy wine sauce, potatoes, broccoli in Hollandaise sauce, coffee, Baked Alaska, and chocolates. At the stroke of midnight, a kilted Highland Cameron bagpiper paraded through the restaurant playing the piper’s lament.

The last tenant to leave the Roxborough Apartments was the Venezuelan Embassy early on 1 October, a few hours after the NCC deadline.

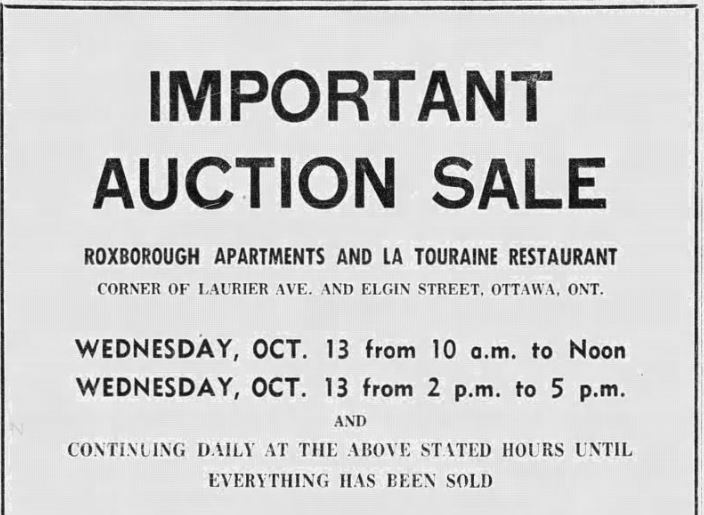

Two weeks later, all the fittings and furnishings in the building and restaurant were sold off to the highest bidder in a multi-day auction. Thousands flocked to the Roxborough to buy a piece of history. One of the most expensive items to be sold was the carpet in La Touraine, complete with the restaurant’s crest woven into the design. It went for $2,000. Even the mail box, the swinging bar doors, and the iron gates and lamp standards that stood at the front door were sold. The big red oak apartment doors were cut into two by fours that sold for 25 cents each.

But this wasn’t quite the end of the Roxborough. Tearing it down proved to be challenging and deadly. Being so close to the sidewalk, the city wouldn’t allow the wrecking company, Eastern Demolishers, to use a wrecking ball to demolish the stone, brick and steel structure. It had to be done by hand. Eastern Demolishers got in repeated trouble for safety violations. But even with safety inspectors frequently on site, Maurice Cardinel, a brother of the company’s owner and father of six, fell six floors to his death in a tragic accident in April 1966. At the subsequent inquest, a Crown attorney said that the method of demolition breached every conceived safety regulation. The jury concluded, however, that a lack of communication between the three levels of government—federal, provincial and municipal—contributed to Cardinel’s death.

With the building levelled, the site of the Roxborough Apartments was turned into a temporary parking lot. In February 1967, Public Works Minister McIlraith indicated his concern about a loss of green space in the area and thought that the new Museum of Human and Natural History might go elsewhere. In the end, it was never built.

The site of the Roxborough Apartments became part of Confederation Park in 1969.

Sources:

Government of Canada, Cabinet conclusions, 1965. “Demolition of Roxborough Apartments,” RG2, Privy Council Office, Series A-5-a Volume 6271, Access Code 90, date 1965-08-04.

Elliott, Andrew, 2022. “History Lost: The Roxy Apt’s,” Blacklock’s Reporter, 7 August.

Mackenzie King, William Lyon, 1923. Diary of W. L. Mackenzie King, Wednesday January 10, 1923, Library and Archives Canada, Item 5734 Jan. 10, Re MG26-J13, 1923.

Ottawa Citizen, 1909. “Of Most Modern Type,” 14 May.

——————-, 1909. “Erecting Many Apartments,” 14 August.

——————-, 1910. “The Roxborough Swings Open Doors To Tenants on May 1,” 26 March.

——————-, 1910. “Looking Around For Real Estate,” 23 July.

——————-, 1965. “NCC to run Roxborough from May 1,” 29 April.

——————-, 1965. “No reprieve to apartment,” 5 August.

——————-, 1965. “Roxborough sold to gov’t,” 1 October.

——————-, 1965. “Nothing left but furniture and memories,” 2 October.

——————-, 1966. “Rush to board up windows,” 6 April.

——————-, 1966. “Falls 6 floors to death,” 9 April.

——————-, 1966. “Demolition firm files for bankruptcy in court here,” 2 June.

——————-, 1966. “A Lady of letters lives at Rideau Hall,” 3 June.

——————-, 1966. “Lack of communications blamed in worker’s death,” 7 June.

——————-, 1967. “Museum may move, use land for parks,” 11 February.

Ottawa Journal, 1910. “The Palatial Roxborough, The Most Modern Apartment House in Ottawa,” 9 April.

——————-, 1910. “Magnificent Interior Woodwork,” 9 April.

——————-, 1910. “Plumbing, Heating and Ventilation, 9 April.

——————-, 1965. “Roxborough Apartments Expropriated.” 21 January.

——————-, 1965. “Save Roxborough Tenants Petition,” 30 April.

——————-, 1965. “A midnight Curfew,” 1 October.

——————-, 1965. “Bidding Hot, Heavy at Auction,” 14 October.

The Windsor Star, 1965. “Battle to Save History,” 1 May.

———————, 1965. “Those Were The …”, 15 October.