30 July 1931

Charles Lindbergh, “the Lone Eagle,” famously made the first, non-stop, solo crossing of the Atlantic in 1927, flying from New York to Paris in his single-engine monoplane, the Spirit of St. Louis. The young aviator quickly captured the imagination of millions on both sides of the Atlantic. Just weeks after his renowned ocean crossing, he flew to Ottawa to help celebrate Canada’s Diamond Jubilee, a trip that was tragically marred by the death of J. Thad Johnson, one of twelve airmen of the 1st Pursuit Group of the US Army Air Service who had accompanied Lindbergh on his trip to Ottawa. Johnson crashed into the ground after a mid-air collision with another member of the flight team.

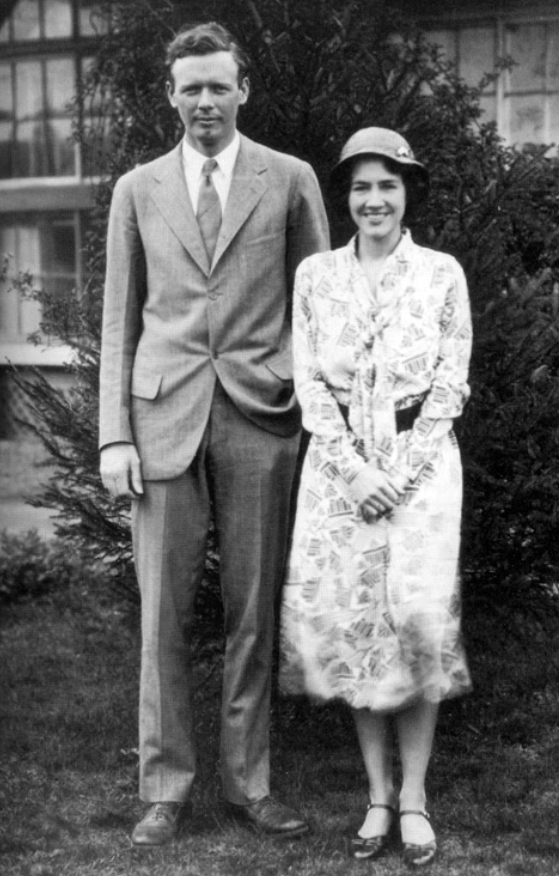

Less well known is Charles Lindbergh’s second trip to Ottawa accompanied by his equally intrepid wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh. She was a pilot, radio operator, and renowned author, as well as her husband’s flying partner in tracing potential air routes for commercial airlines. The couple stopped in Ottawa in 1931 as they made their way in stages across Canada on a journey to the Far East. Anne Morrow Lindberg later chronicled their trip in a book called North to the Orient, published in 1935.

Anne Morrow was born in 1906, the daughter of Dwight and Elizabeth Cutter Morrow. Dwight Morrow was a partner in the financial firm J.P. Morgan and was one of the richest men in the United States. He later became a very successful and well-respected US ambassador to Mexico and was subsequently first appointed, then elected, to the US Senate. Elizabeth Cutter Morrow was a champion of women’s education, poet, and author of children’s books.

Their daughter Anne met her future husband in Mexico City in late 1927. She was just twenty-one years old. Lindbergh had been invited to Mexico by her father as a goodwill gesture towards the Mexican government. The couple married two years later. Their first child, Charles Junior, was born in June 1930.

The following year, the Lindberghs set off on a daring trip to the Far East. This was a journey of considerable peril as flying was still in its infancy. There were few airports, and little in the way of air traffic control, or even communications along their route which stretched across northern Canada, Alaska and Siberia before reaching the Japanese archipelago. Anne Lindbergh described their journey in the following terms: Our route was new; the air untravelled; the conditions unknown; the stories mythical; the maps, pale, pink, and indefinite, except for a few names… Despite the known and unknown perils involved, the trip was for “pleasure” though many assumed that the couple were scouting out possible routes for commercial air traffic between New York and Tokyo.

Before commencing their journey, the couple undertook extensive preparations. Both learnt how to operate a radio, though it was Anne who assumed responsibility for communications. To receive the necessary third-class radio licences, both passed a Morse Code test of at least fifteen words a minute and were quizzed on the care, operation, and repair of the radio, and on US communication laws and regulations. The Lindberghs also had to plan their route, organize fuel supplies at their many stops, and to equip themselves in the event of emergency. While Charles Lindbergh was the primary pilot on the journey, Anne also flew their craft on the longer flights to allow her husband to sleep.

Their dual cockpit, Lockheed Sirius 8 monoplane, the NR-211, with the call letters KHCAL, was equipped with a single 600hp cyclone engine and pontoons to enable it to land on inland lakes and rivers as well as on protected ocean bays. The airplane could carry roughly 600 gallons of fuel in its wings and pontoons, giving it a range of 2,000 miles with a normal cruising speed of only 105 miles per hour. Their general equipment consisted of instruments for night and “blind” flying, something they wanted to avoid, a radio (which included a long hand-cranked antenna ending with a ball-weight that stretched out behind the airplane when in flight), compass, and gear necessary for refueling and anchoring. Other emergency supplies included, a repair kit, rubber boat, sail and oars, a backup radio, parachutes, camping equipment, 47 pounds of emergency rations, revolvers, a .22 rifle, ammunition, a medical kit, and warm flying clothes. In choosing these items, weight had to be balanced against usefulness. According to Anne, they weighed everything on baby scales.

Charles and Anne Lindbergh officially started their trip to the Orient on 27 July 1931, departing from College Point, Long Island to go to Washington D.C. to pick up necessary passports and other documents. (Lindy Flies to Capital for Hop To Japan.) Prior to their departure, the couple were deluged by reporters’ questions. In North to the Orient, Anne described her dismay when asked “conventional feminine questions” about her clothes, and where she had stored the box lunches for the trip. After the brief stop in Washington, the Lindberghs left for North Haven, Maine, the location of her parents’ summer home.

Anne said that the real start of their adventure was their departure from North Haven bound for Ottawa in the early afternoon of Thursday, 30 July 1931, leaving their young son, Charles Jr., in the care of her parents. It took 3 hours and 24 minutes to fly the 370 miles to Canada’s capital. Every fifteen minutes, Anne contacted one of two tracking stations, updating their position and to ask about weather conditions.

Fifteen hundred Ottawa residents were on hand at the Rockcliffe aerodrome to await the arrival of the Lindberghs. At about 4:15pm, a frisson of excitement ran through the crowd as a yellow monoplane flew across the sky from the south. But it wasn’t the famous couple, but rather a plane flown by Captain James Goodwin Hall, who was accompanied by a news photographer. They had raced ahead to take photographs of the Lindberghs’ arrival in Ottawa. (Captain Hall was another famous aviator, and at that time held the record for a non-stop flight from New York City to Havana, Cuba.) Charles and Anne Lindbergh arrived in Ottawa at shortly after 5:30pm, landing on the Ottawa River near the Rockcliffe aerodrome. With a stiff 30 mile-per-hour wind blowing, Charles Lindbergh made two passes over the Ottawa River before landing their black and red seaplane on the choppy water.

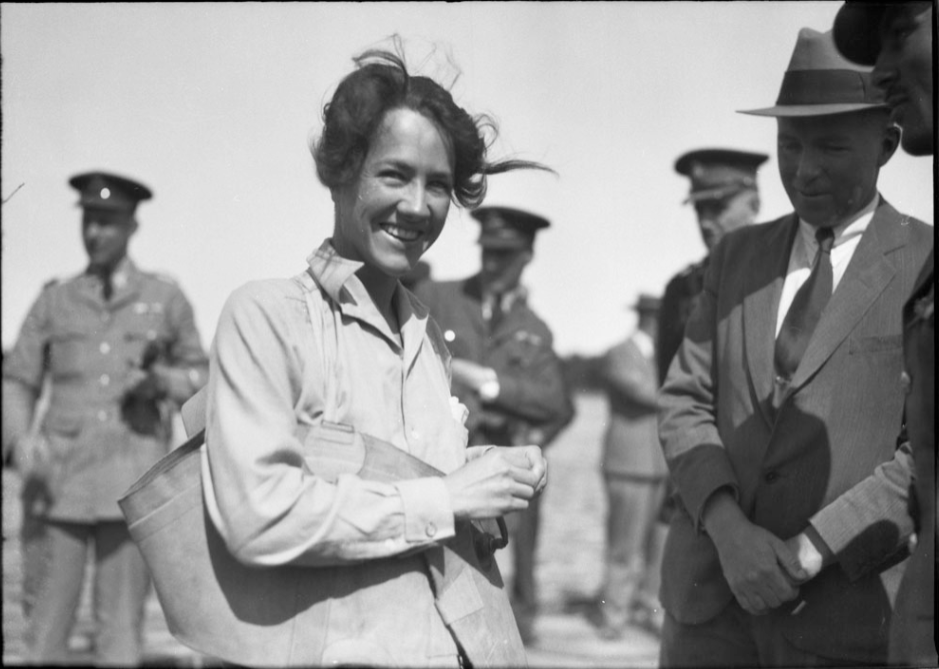

He taxied several hundred yards to a special mooring to which he fastened the aircraft. Two servicemen waited in a small outboard boat. One cried out “Hello Lindy. How are you?” Lindbergh waved and responded: “Hello. Fine.” After safely securing his aircraft, he and his wife were transported by the small outboard boat to a larger launch for the short journey to the wharf. Alighting from the launch, the couple were greeted by a mass of journalists and photographers, as well as raindrops. The deteriorating weather didn’t dampen the enthusiasm of the crowd of Lindbergh admirers restrained by six RCMP officers in their scarlet dress uniforms who also provided the couple a guard of honour. The Citizen reported that there were shouts of “Good Old Lindy.” And “Hello, Mrs. Lindbergh.”

The couple was officially greeted by Colonel MacNider, the US Minister (Ambassador) to Ottawa, Mrs. MacNider, and Wing Commander Godfrey, the commanding officer of the air base. Charles and Anne Lindbergh got into the back of Colonel MacNider’s car, with the US Minister behind the wheel, to drive to the MacNiders’ Rockcliffe home where the Lindberghs would stay the night during their brief stay in Ottawa.

That evening, Colonel and Mrs. MacNider hosted an informal dinner in honour of the Lindbergh couple. The Prime Minister, R.B. Bennett, was forced to decline their invitation to attend owing to Parliament sitting. Instead, he came before breakfast the next morning to wish the couple “God Speed.” At the dinner, Anne Lindbergh was seated beside one of the foremost Canadian experts on the radio. She wrote that she was “slightly ruffled” by this owing to her inexperience in operating radio equipment. Meanwhile, her husband talked to Canadian aviators experienced with flying in the Canadian north, seeking advice on air routes. The Canadian flyers tried to dissuade him from flying his chosen route northward. According to Anne, the flyers’ efforts were as effective as adults talking to a little boy about the dangers of playing with firecrackers. She also noted with pleasure and pride that when somebody said to her husband “I wouldn’t take my wife over that,” Charles Lindbergh replied that she was “crew.” She wondered: “Have I then reached a stage where I am considered on equal footing with men?”

With their airplane refueled overnight, Anne and Charles Lindbergh left the MacNider home shortly after 9am to go to the Rockcliffe aerodrome for the final pre-flight checks for their flight to Moose Factory on the Hudson Bay, the next stop on their journey to the Orient. As the plane took off shortly before 11am, the couple waved from the cockpit to the big crowd of well-wishers, who included not only Col. And Mrs. MacNider, but also Major General Andrew G. McNaughton, Chief of the Canadian General Staff, and his wife, and Sir William Clark, the British High Commissioner, and Lady Clark. Their 460-mile flight took them over the Gatineau Hills, and Amos, Quebec in the Abitibi region, then north to Moose Factory.

From Moose Factory at the southern end of the James Bay, the Lindberghs headed northwest, stopping briefly at Churchill, and Baker Lake, before tackling the arduous twelve-hour flight to the small community of Aklavik in the Mackenzie Delta. The last stage was flown during the twilight of an Arctic summer’s night. From time to time, Anne Lindbergh took the controls to allow her husband to sleep. From Aklavik, they left Canadian air space, landing first in Port Barrow, then in Nome, Alaska, but not before being forced down by thick fog to spend the night in a lonely lake before being able to resume their journey.

From Nome, the couple left for Siberia, crossing the Bering Straits and the international date line. After two stops at Karaginski and Petropavlovsk on the Kamchatka Peninsula, Charles and Anne ventured down through the Kuril Island chain, then Japanese territory (but later seized by the Soviet Union in the dying days of the Second World War, their Japanese population expelled). Fog again brought the couple down, this time at Shimushiru Island, also known as Simushir. The Lindberghs’ aircraft was assisted into the sheltered harbour of the small community of Broughton Bay at the north end of the island by a Japanese ship. (Broughton Bay later became a Soviet naval base; the island is now uninhabited.)

Nemuro in Hokkaido was the Lindberghs’ first stop on the main Japanese Islands. This was followed by stops in Tokyo, Kyoto and Fukuoka. Surprisingly, Anne says relatively little about their stay in Japan though she did write about the warm welcome they received. One particular incident of note was the discovery in Osaka of a stowaway—a Japanese youth in school clothes curled up in their baggage area. Cramped in a tiny area, the poor lad could hardly stand after being pulled out. For food, he only had a few gumdrops in his pocket. It seemed that he wanted to go to the United States, unaware that the couple was headed to China.

The last stage of their trip to the Orient, and their most arduous, was the trip to Nanking, China where they helped survey the disastrous flooded Yangtze River valley on behalf of China’s National Flood Relief Commission. This was a harrowing and dangerous occupation. At one point, their seaplane was surrounded by sampans crowded with starving people looking for food. It was only after Charles Lindbergh pulled his revolver that they were able to fly away unscathed. At another occasion, the British aircraft carrier HMS Hermes winched the Sirius onboard to avoid it being rammed by Chinese boats. (The Hermes was the first ship to be designed as an aircraft carrier, and was at that time stationed in China assisting the Chinese government with mapping the extent of the Yangtze flooding.) Subsequently, the Lindberghs’ aircraft was damaged by a gust of wind when it was being relaunched, leaving it holed in several places. Both Charles and Anne, both fortunately wearing life jackets, had to jump into the Yangtze River and be rescued.

Charles and Anne Lindbergh made their way back to Japan via ship. After crossing Japan by train, they left the country from the port of Yokohama to return to the United States.

The following year, their lives were upended by the kidnapping and murder of little Charles Jr. for which the German immigrant, Richard Hauptman, was later found guilty in the “trial of the century.” Hauptman later died in the electric chair. Following the death of their son, the couple went into seclusion in England until 1939.

Charles Lindbergh became associated with the isolationist America First Committee movement that argued against US involvement in another European war. He even objected to military support for Britain. Some prominent members of the Committee also professed anti-Semitic and pro-fascist views, something that tarnished Lindbergh’s reputation. Lindbergh changed his mind after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor but the damage was done. He later flew in the Pacific theatre as a civilian pilot. After the war, he became an avid environmentalist and award-winning author. He died in 1974. After his death, it was revealed that Lindbergh had had a lengthy, secret relationship with a German woman with whom he had three children.

After the tragic death of their first child, Anne and Charles Lindbergh went on to have five more children—sons, Jon, Land, Scott, and daughters, Anne and Reeve. Anne’s first book North to the Orient, published in 1935, was an instant bestseller and won the National Book Award. (For Ottawa residents, a copy of the book can still be found in the Ottawa Public Library.) She went on to write many other books and poems. Her diaries and letters were published in the 1990s. Anne also received many honours for her role in early aviation, including the exploration of air routes with her husband. Anne Morrow Lindbergh died in 2001.

The Lindberghs’ aircraft, Sirius, is on display at the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C.

Sources:

Lindbergh, Anne Morrow, 1935. North To The Orient, New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Ottawa Citizen, 1931. Lindberghs Are In Capital On Trip to Orient,” 31 July.

——————, 1931. “Lindbergh Sees No Real Hazard Present Flight,” 31 July.

——————, 1931. “Weather Report Favors Fliers For Their Hop,” 1 August.

Ottawa Journal, 1931. “Noted Flying Couple Arrive At Rockcliffe,” 31 July.

Very interesting reading this James..

Good to see this side of the Lindbergh family.

LikeLike

Many thanks for taking the time to send me a comment. Best wishes, James

LikeLike